It is certainly an interesting time to be considering the role of the financial system says Mick McAteer of the Financial Inclusion Centre. The social utility of financial markets and their contribution to the climate crisis is under intense scrutiny and the credibility of, and trust in, the sector remains low due to the role it played in the financial crisis of 2008 and a litany of mis-selling scandals.

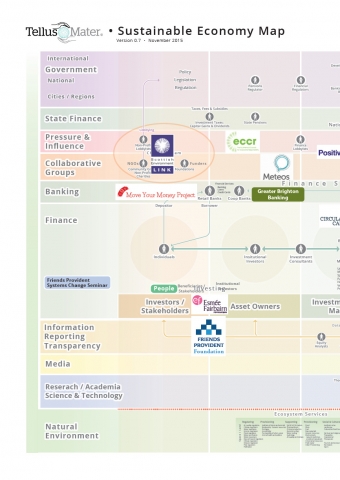

There would seem to be a growing consensus that, to tackle the climate crisis, we need to change:

- the way we live: the choices we make about how and what we consume.

- the way we work and produce: the nature of economic activity and the corporate behaviours society expects.

- the way the financial system works: the allocation of resources by financial institutions, and the choices we make about how our money is used.

- the way the global markets are governed and regulated: the climate crisis is a truly global issue and so requires a global, collaborative approach to governance and regulation.

Benchmark interest rates and government bond yields were driven down in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. The effects are still being felt today. Savers, investors, and pension scheme members are exposed to new financial risks, while the allocation of financial resources to the real economy has been distorted.

The financial system is under renewed stress driven by fears of the potential economic impacts of the Coronavirus and disruption in the oil markets. It is likely to be some time before interest rates and bond yields return to typical pre-crisis levels (if they ever do).

But, this ‘new normal’ of low interest and bond rates should also create opportunities for finance for good – sustainable, responsible and social impact activities which we refer to collectively as SRI. Financial institutions and households are looking for ways to generate decent returns to offset the low yields on deposits and bonds (the ‘search for yield’). The sheer scale of the assets available in financial markets and savings, investment and pensions portfolios creates opportunities to channel significant resources into SRI activities. This report, therefore, set out to assess the potential for SRI growth. To do so, we asked two questions:

Our findings confirm that SRI has indeed moved up the agenda, attitudes have become more positive, and there has been some growth in assets allocated to the sector. But, it must be said, there is a long way to go before SRI is mainstreamed into financial markets.

The proportion of total assets held by financial institutions and households in SRI remains very low – particularly seen against the amount invested in alternatives (such as hedge funds or private equity), banks have lent to other parts of the financial system or to the property market, and households have invested in the buy-to-let property market. On the retail investment side, just 1.4 percent of total assets under management are invested in ethical funds.

Globally, the value of funds managed with explicit environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria is still under one percent of total global assets under management. ESG assets under management would seem to be growing at a slower rate than mainstream assets under management. Similarly, green bonds represent a small fraction of the vast global bond markets.

Despite the hype about shareholder engagement, UK company boards are not coming under sustained pressure from shareholders to realign company operations to SRI goals. The UK scores poorly on issuing green bonds for domestic use compared to countries like France and Germany – both with smaller financial centres. The UK has not met its targets for direct investment in clean energy projects. Bank direct lending to green projects has also been disappointing, while the Bank of England’s QE programmeme has been skewed towards high carbon sectors of the economy. It is not surprising therefore that the level of economic activity in the green sector has also been disappointing still representing around one percent of total economy turnover.

So, what needs to be done? There are a number of existing, effective civil society and market-led initiatives designed to promote greater use of SRI. But our analysis of the structural barriers tells us these are unlikely to go far enough to change minds and behaviours, and to mainstream SRI into financial markets. We make 41 specific policy recommendations grouped around the core policy aims of:

- Increasing the availability of quality, consistent, trustworthy SRI information, research, and analysis

- Raising awareness of and promoting confidence in SRI assets

- Encouraging investors, lenders, and intermediaries to engage with SRI

- Embedding SRI into decisions made by lenders, investors, and financial intermediaries

- Better aligning financial market behaviours with SRI goals

- Creating a more supportive regulatory architecture

- Ultimately, increasing the resources allocated to SRI by the public and private sector.